Forty years ago, our colleague Dick Bouman’s lifetime commitment to water and development started in East Africa with his job as a junior hydrologist. On October 1, 2006, he joined Aqua for All to contribute to the development of the water and sanitation sector. Today, 15 years later, Dick continues working to make water and sanitation accessible for all as Aqua for All’s Regional Manager Horn of Africa.

Dick’s blog is a personal account of his experiences with organisations in the water and sanitation sector all over the world.

How it started

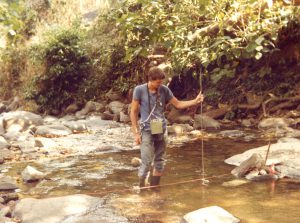

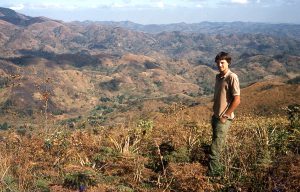

40 years ago, in August 1981, I started my career in development cooperation working for DHV, a Dutch consultancy company (today part of Royal Haskoning DHV). I got a half-year assignment as junior hydrologist in the Southern Morogoro Region in Central Tanzania.

But this choice had a longer history. As a teenager, I volunteered in my village for ‘Kom over de Brug’ (Cross the Bridge), the first national interchurched fundraising event for development aid. I was raised with strong values and beliefs, and a strong orientation towards creating a fairer world.

The option to go abroad determined my choice to study Physical Geography and Hydrology at the Vrije Universiteit. I took extra courses on Development Studies with famous lecturers, such as Prof. Galtung on the development bias between urban centres and the periphery, and Prof. De Gaaij Fortman. I actively lobbied to make the hydrology curriculum more appropriate and practical for working in tropical countries. My motivation came from the first UN Water Conference in Mar del Plata, where the first International Water Decade was proclaimed (1980-1990).

Promoting ‘Appropriate Technology’

In the seventies, ‘Appropriate Technology’ was proposed as an alternative to ‘western’ technology. DHV promoted ‘Appropriate Technology’ in its Shinyanga Shallow Wells project, which used manual digging and drilling technology, and a robust hand pump made of locally available materials. DHV had a strong impact on making ‘Appropriate Technology’ fashionable, even among commercial companies.

At this time, Tanzania’s social and economic development policies were guided by the Ujamaa model. Rural people had to migrate to larger villages where basic services would be arranged by the authorities. By 1981, the model had become less popular, following years of poor harvest and economical decay. Power was used to force people in the ‘right’ direction, and local traditions and traditional power structures were overruled.

From project to programmes

When I arrived in Tanzania, petrol was restricted and prices were high. A dependency attitude reigned in all levels of society. Only a few people realised that the promised ‘free’ access to basic needs was not sustainable. And the optimistic view of a ‘maakbare samenleving’ (‘engineerable society‘) had also decayed.

At the same time, my expectations on my employer’s development approach required rectification. The company had adopted a greater technical approach than what was originally planned. It regarded the Kangaroo foot pump to be maintenance-free and therefore any form of capacity building was neglected. Community participation was reduced to a joint mapping exercise to select the best place for the water point.

In 1983, I published my findings in ‘Door techniek alleen, beperktheid van een puttenproject in Tanzania’ (‘By technology only; limitations of a shallow well project in Tanzania’).

Five years later, a Finnish scholar published a review of the Scandinavian and Dutch regional bilateral water programmes called ‘Watering White Elephants? Lessons from Donor Funded Planning and Implementation of Rural Water Supplies in Tanzania’. The Morogoro project was extensively reviewed in the chapter ‘The Turn key ‘approach’ with a salesmen’s touch’. The report concluded that water development organisations had taken over the coordination from the local authorities.

This was the time when the ‘project approach’ was being replaced by a more programmatic approach, but this turned out to be not the silver bullet. Many integrated rural development programmes failed, because it was hard to integrate all programme elements, especially those under different ministries and with different timelines.

A defining moment

Paradoxically, I had also embraced a stronger project focus without noticing, despite my beliefs and training on development theories and institutional issues. This narrow focus resulted partly from a culture of consultancy contracts that are time-bound and restricted by clear Terms of Reference.

As a young expert, I sometimes felt lost in this discouraging context. I missed a culture of reflection. Fortunately, I found it again when I was selected to do my social service in 1982/83 by the ‘Vereniging Werkgroep Waterbeheer’. This volunteer organisation was created by water professionals to support ‘volunteering’ water experts primarily in Portuguese speaking countries in Africa. In 1984, ‘Werkgroep Waterbeheer’ created ‘Stichting SAWA for WASH and Irrigation’, a non-profit consultancy company. This new opportunity kept me involved in this work for over four decades.

My experience working in Mozambique for three years (1984-1987) was as important as my time in Tanzania. Mozambique had few water professionals and preferred contracting individual experts from abroad (‘cooperantes’), instead of outsourcing programmes to companies or development organisations from abroad. This paved the way for the years to come; first at SAWA and afterwards as a consultant.

My first years at Aqua for All

From 1999 until 2006, I worked for ‘Kerkinactie/ICCO’, a Dutch faith-based development organisation. I held different positions ranging from fund manager for emergencies in the Balkan states to policy advisor on several development issues, except for water.

Turning 50 and the death of my father made me think about my future. I longed to return to my real area of expertise for the last 15 years of my career.

In 2006, I joined Aqua for All. The organisation’s purpose, size and culture resembled those of my first working environments. I was also attracted by its close ties with the Dutch water sector, its innovative fundraising concept and its visionary director (Sjef Ernes). However, its development approach was still rather traditional and project-based. Working with large players, such as Vitens and UNICEF, small private initiatives and many volunteers from the water sector was very attractive.

From followers to frontrunners

Over the years, several water sector partners developed their own programmes, and since 2012, Aqua for All was not allowed to use its grants to support small development non-governmental organisations. This situation and the vision of our former director drove the change in our development approach.

We became a frontrunner by exploring new approaches to accelerate access to water and sanitation through supporting enterprises and solutions with a high potential to scale. My role was mainly to manage the project portfolio. Later, it changed into managing the project desk, monitoring key indicators and making sure we fulfil our promises towards our donors.

In 2016, I made a major shift by stepping down from this function to become Fund Manager of the VIA Water Innovation Fund, which was linked to Aqua for All. I was very motivated by this opportunity to work with partners in low-income and developing countries in a more direct way.

The Innovation programme brought positive change. We strengthened our learning attitude and orientation towards innovation, and included international staff.

The beauty of the field

Looking back, I am sometimes jealous of those working on concrete projects. Being in the field, ‘reading the landscape’, and talking with African people always gave me a thrill. These were the skills that I have insufficiently used during most part of my career.

It is somehow the faith of many academics to get more managerial jobs when getting older. Once I had the chance to step into a university career, but I turned it down. I chose to remain involved in concrete projects as much as I could, by sharing my insights with partners; whether requested or not. And I am happy that I still can use these skills, even though mainly from behind my desk.

Luckily, I can still practice hydrology on my green roof and with a pond and wadi in my garden. After long stays in East and Southern Africa, I visited other parts of Africa and the world. During my first visit to Ghana (1991), I was very impressed by Ghanaians’ autonomous attitude. In North East Somalia (1994), I was touched by the deep cultural rooting of the clan structures. In Palestine/West Bank (1995), I learned about the impact of history and politics. In Guatemala and in Papua New Guinea, I realised it is impossible to learn about the more deeper parts of the local cultures in a few weeks’ trip.

Learning by doing has been my approach in consultancy work, and having the courage to explore new fields. When I was asked in 1989 to do a preparatory study for a large Dutch urban drainage and sewerage project in Maputo, I knew the language, the city and the people; but was no expert in sanitation. Common sense can bring you far and I was happy that the contracting company had expressed their trust in me. Young people need to be encouraged to explore these new fields in practice.

My lessons in life

When asked for my ‘Aha!’ moments, I recall two situations. The first one was during my first week in Africa. The pessimistic columns in Dutch newspapers on the crime in Dar es Salaam impacted me enormously. This led to develop a kind of distrust in people. Fortunately, one experience changed my mind completely: While waiting in a row, the woman in front of me turned and offered me an orange without asking for anything in return. Then I realised that I should approach people with trust, instead of distrust.

Another moment was during an alumni meeting. A much younger hydrologist told me that she had chosen for this study because of my enthusiasm when I guided her and a group of high school pupils from Breda (the Netherlands) at a dam site in Mozambique. This made me aware of the positive impact a person can have just by being passionate about something.

We are getting there

Many things have been achieved in the last four decades and I feel proud that I took the chance to make a small contribution to this.

Billions of people now have access to water for the first time in their life. We work towards making water services safer and more reliable. As more people move away from poverty, they can afford these basic needs. There is still dependency, but I expect it will be reduced in the coming years. The rapid increase of the amount of local water and sanitation professionals will allow the countries to develop, based on their own capacities.

I’m getting closer to turn 66 years old, and I am celebrating 15 years at Aqua for All and 40 years working in the water sector. The truth is I am not ready to step out now or in a year when my formal retirement date arrives. I will continue looking forward as I did back then in 1981. With more time, I see myself drawing lessons and transferring my knowledge and experiences to fellow colleagues and partners abroad, without hard deadlines and not only from behind a desk.